#19 · 2-7-26 · Age of Revolutions

Ludwig van Beethoven

Composer of Defiance and Devotion

1770–1827

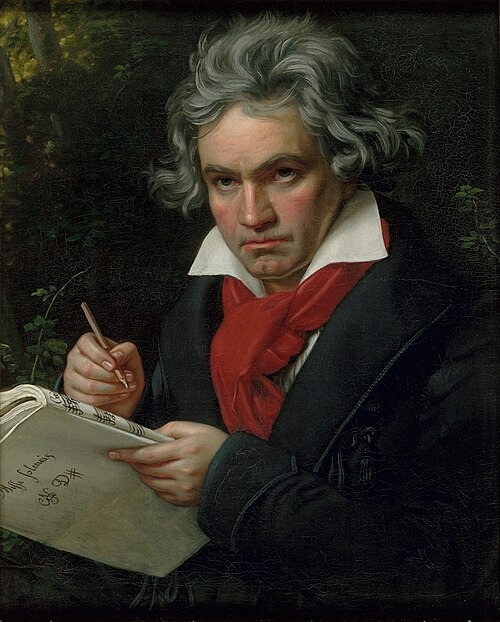

AI-assisted Portrait of Ludwig van Beethoven.

The Sound That Refused to Yield

Born in 1770 in Bonn, Ludwig van Beethoven entered a household shaped by volatility and ambition. His father, a struggling court musician, attempted to mold him into a prodigy through force rather than encouragement. Practice sessions were relentless. Praise was scarce. Neighbors reported the child in tears at the keyboard.

His mother, by contrast, was described as gentle and steady — the emotional refuge of his early life. When she died while he was still a teenager, Beethoven effectively became head of the household, managing finances and caring for his younger brothers as his father declined into alcoholism.

Responsibility arrived early. Stability did not.

By the time he settled in Vienna, Beethoven carried not only extraordinary talent, but also pride sharpened by hardship. Deafness would later isolate him further, amplifying both his intensity and his resolve. What emerged from that life was not detached intellectualism, but music that felt carved from lived emotional force — urgent, embodied, unyielding.

Beethoven mattered not simply because he expanded musical form, but because he transformed suffering into structure without diluting its intensity.

The Psychological Verdict

Beethoven is often typed as INTJ due to the architectural power of his compositions. Yet intimate accounts and personal writings suggest a different cognitive orientation.

Rather than leading with detached vision, Beethoven appears to have led with deeply internalized value intensity — emotion forged inward first, then expressed outward through craft.

The evidence aligns more convincingly with ISFP.

Fi — dominant

Contemporaries repeatedly described Beethoven as hypersensitive, proud, morally intense, and easily wounded. He reacted strongly to perceived slights and guarded his dignity fiercely. His letters are personal and emotionally absolute rather than conceptually structured.

The Heiligenstadt Testament reads as a private moral reckoning — not a strategic manifesto, but a confession of shame, despair, and inner resolve. His language centers on honor, virtue, and being misunderstood.

This is not emotional detachment. It is inwardly anchored conviction.

Beethoven did not adjust himself to fit social expectations. He preserved internal integrity even at personal cost. That constancy of inner value is characteristic of dominant Fi.

Se — auxiliary

His relationship to music was physical and immersive. Witnesses described him attacking the piano with intensity, embodying sound rather than delicately shaping it. His compositions expand emotional force through dynamic contrast, rhythmic propulsion, and sensory immediacy.

Even the famous opening of the Fifth Symphony does not wander through possibility — it strikes. It asserts.

Se auxiliary supports this embodied artistry. The medium was not abstract theory; it was lived sensation translated into form.

His obsessive revisions can be understood not as system-building for its own sake, but as refinement of impact. The sound had to feel right.

Ni — tertiary

The structural cohesion of his large works does not require dominant Ni. Tertiary Ni can manifest as thematic convergence over time, especially in a gifted artist.

In the late quartets, abstraction deepens — yet the music remains emotionally grounded rather than conceptually detached. The inwardness intensifies, but it does not become clinical.

The architecture appears to arise from emotional necessity rather than strategic blueprinting.

Te — inferior (developed under pressure)

Beethoven’s personal life was notoriously chaotic. His apartment was disordered. His finances fluctuated. Social interactions were volatile.

Yet in composition, he demonstrated rigorous revision and technical control.

Inferior Te in ISFPs can become highly developed, particularly when early life demands responsibility. After his mother’s death, Beethoven assumed financial and familial duties as a teenager. Structure became survival.

The discipline in his music appears domain-specific and hard-earned — not a globally organized temperament, but a tool forged through pressure.

Why Not INTJ?

INTJs are typically described as internally composed, strategically consistent, and emotionally contained. Beethoven was described by intimates as combustible, reactive, and deeply personally wounded.

His letters do not display Ni–Te clarity. They display Fi intensity mediated through craft.

The architectural strength of his compositions can be explained by mastery, training, and developed Te — it does not necessitate Ni dominance.

Structure in his work does not point to emotional suppression. It points to emotional transformation.

The Inner Strain

Understanding Beethoven as ISFP reframes his life more coherently.

A child pressured into performance.

A young man forced into responsibility.

An adult increasingly isolated by deafness.

For a dominant Fi temperament, such conditions would not extinguish feeling. They would intensify it — and seek an outlet strong enough to contain it.

Music became that outlet.

Not escape.

Not theory.

But embodiment.

Historical Figure MBTI

Historical Figure MBTI