#22 · 2-8-26 · The Long Century

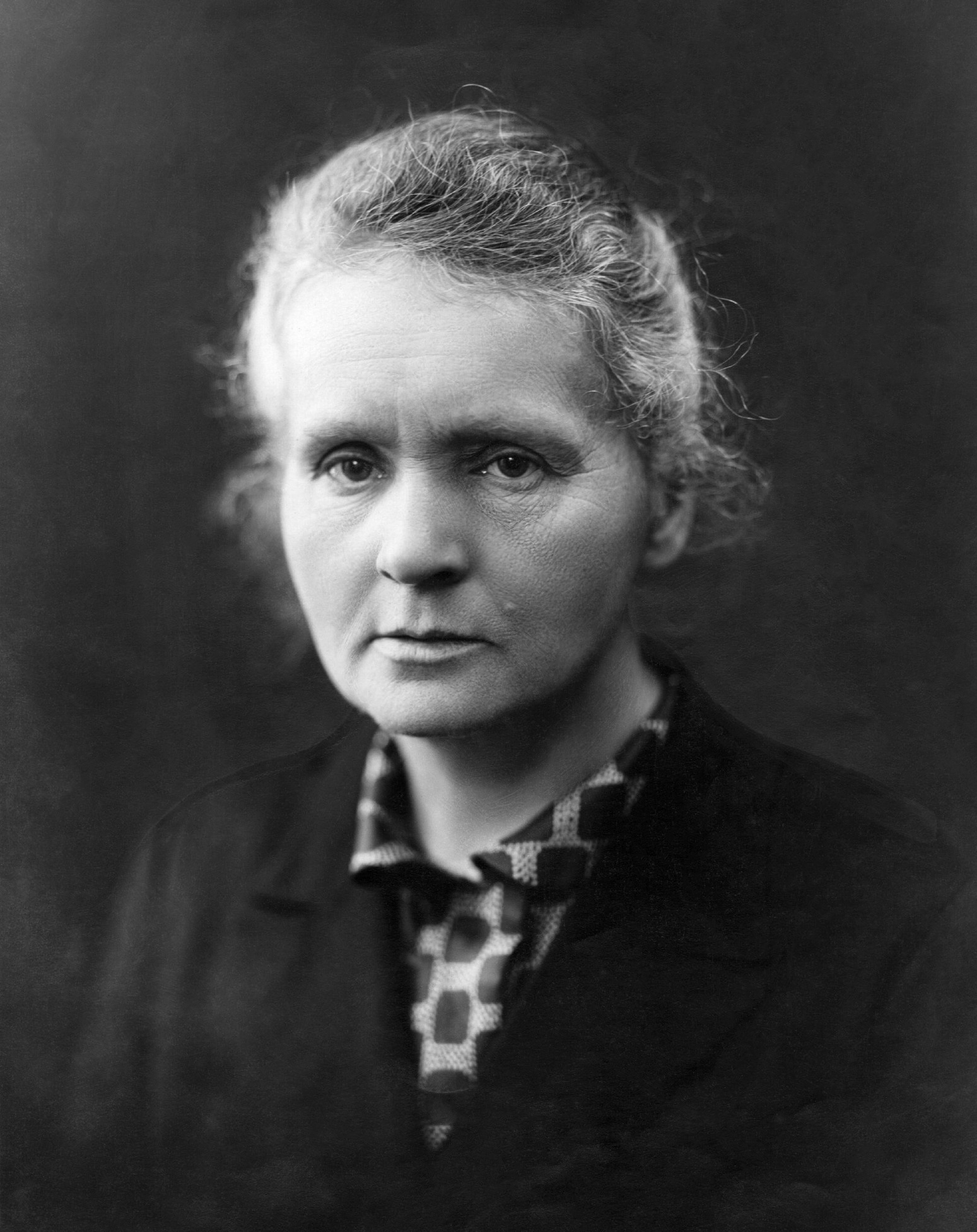

Marie Curie

Physicist, chemist, and architect of radioactivity

1867–1934

Portrait of Marie Curie.

The Weight of Continuation

Marie Curie did not live a life designed for brilliance.

She was born into political erasure, educated in secret, and shaped early by loss. Opportunity was delayed, constrained, and rationed. And yet — once she identified her path, she never deviated from it. Her life reads not as a sequence of inspirations, but as a single, unbroken line of continuation.

Where others slowed under hardship, Curie compressed. Where recognition failed to arrive, she continued anyway. This was not resilience for show. It was a quieter conviction: that truth, once perceived, demands completion — regardless of cost.

She did not chase discovery. She endured toward it.

The Psychological Verdict

Marie Curie is frequently typed as an INTP — quiet, analytical, withdrawn, theoretical. On the surface, this seems plausible. But a closer examination of her cognitive patterns, work process, and emotional regulation suggests a different structure.

Curie was not a model-builder circling questions for intellectual satisfaction. She was a truth-extractor — selecting a problem, committing to it fully, and enduring reality until it yielded a definitive answer.

This pattern aligns far more closely with INTJ.

Ni — Dominant

Curie’s thinking was vision-led and unbranching. Once she identified radioactivity as a coherent phenomenon, she did not wander between hypotheses. She named it early, defined its scope, and oriented years of labor toward uncovering its underlying properties.

Her research trajectory was linear and compressive: fewer questions over time, greater depth, increasing inevitability. This is classic Ni — an internal certainty guiding prolonged focus, not curiosity hopping between possibilities.

She did not ask what else could this be? She asked what is this, fundamentally — and how far does it go?

Te — Auxiliary

Curie’s work ethic was famously severe. She subjected herself to years of repetitive, physically exhausting labor, processing tons of raw material by hand to isolate minute quantities of radium and polonium.

This was not exploratory tinkering. It was execution in service of a known goal.

Her writing reflects the same orientation: sparse, declarative, results-focused. She wrote to formalize conclusions, not to think aloud. Theory was always instrumental — valuable only insofar as it enabled extraction, proof, and application.

During World War I, this Te axis became unmistakable. She pivoted her knowledge into mobile X-ray units, personally deploying them at the front. No rhetoric. No hesitation. Just applied vision under pressure.

Fi — Tertiary

Curie’s values were internal, rigid, and non-negotiable. She refused to patent her discoveries, believing scientific knowledge belonged to humanity — even at personal financial cost. She named polonium after her occupied homeland, a quiet act of loyalty rather than public protest.

In personal life, she showed little interest in reputation management. During public scandal, she did not explain herself. She did not defend her character. She continued working.

Her journals reveal not emotional exploration, but emotional containment. Grief is acknowledged, then subordinated to obligation. Feeling exists — but it does not lead.

Se — Inferior

Curie’s relationship with the physical world was sacrificial. Her body bore the consequences of prolonged radiation exposure. She ignored physical limits, comfort, and safety in service of insight.

This is not sensory attunement. It is inferior Se — an uneasy, obsessive engagement with the material world as a means to feed higher-order understanding, often at great cost.

Her death from radiation-related illness stands as a final testament: the body spent to complete the vision.

Why Not INTP?

An INTP approach would have emphasized internal model refinement, hypothesis cycling, and conceptual play. We would expect writing that circles uncertainty, journals that interrogate emotion, and a work pattern that follows interest rather than endurance.

Curie did none of these.

She did not write to understand her feelings. She wrote to contain them. She did not theorize endlessly. She committed decisively. She did not stop when novelty faded. She continued until completion.

Her science was not exploratory — it was extractive. Her thinking was not open-ended — it was convergent.

She did not ask permission from uncertainty.

The Partnership That Clarified Her Type

Marie Curie’s INTJ structure becomes clearer in contrast with Pierre Curie. Pierre was brilliant, principled, and intellectually refined — but less directed. After meeting Marie, his work gained coherence and momentum.

She provided the spine.

Their relationship was not romantic spectacle but shared construction: two minds aligned around a single axis of truth. When Pierre died, Marie did not collapse into reflection. She assumed his role and continued the work.

That continuation — without replacement, without deviation — reveals the core of her cognition.

Historical Figure MBTI

Historical Figure MBTI