#1 · 1-22-26 · The Renaissance

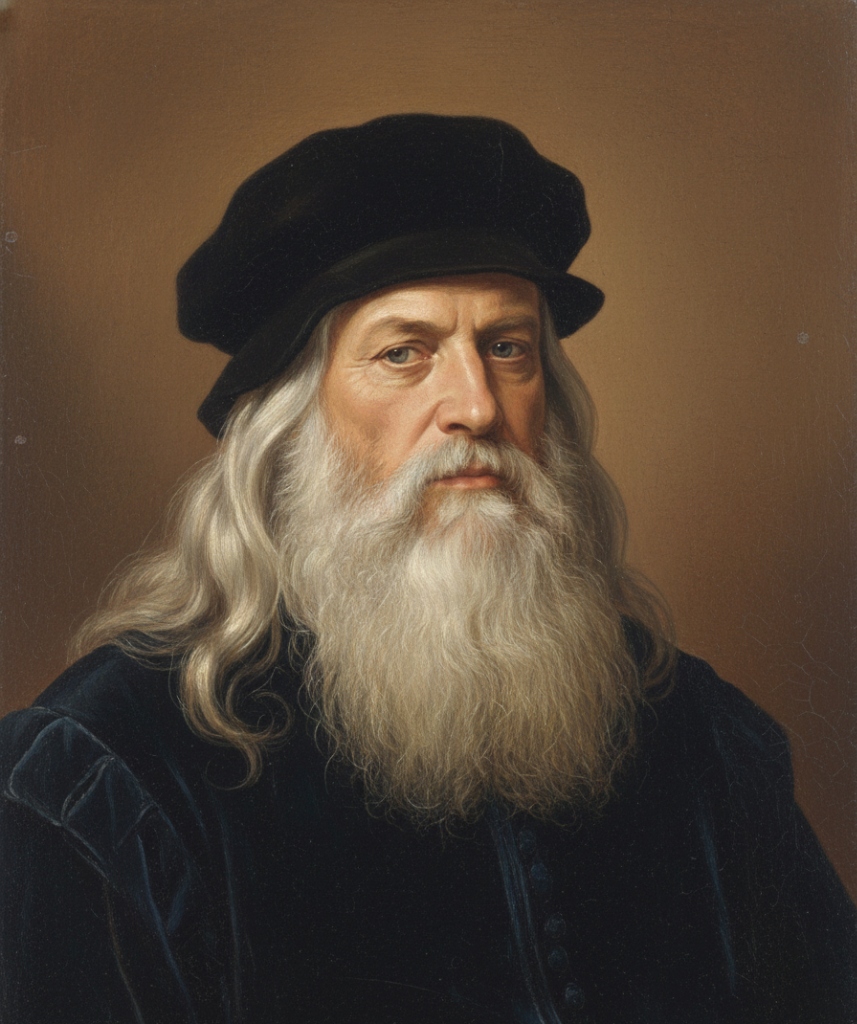

Leonardo da Vinci

Polymath, painter, engineer, and architect of the High Renaissance.

1452–1519

AI-assisted Portrait of Leonardo da Vinci

The Universal Man

Born on April 15, 1452, in the small Tuscan town of Vinci, Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci would become the quintessential "Universal Man" of the Renaissance. His life was a relentless pursuit of knowledge, spanning art, science, engineering, and philosophy. He saw no boundaries between these disciplines, believing that to understand the beauty of a painting, one must first understand the mechanics of light and the anatomy of the human form.

Leonardo's values were rooted in direct observation and the belief that nature was the ultimate teacher. In an era often dominated by dogma, he insisted on empirical evidence and the power of the human mind to synthesize complex patterns into unified truths.

The Psychological Verdict

While often debated and frequently categorized as an ENTP due to his vast range of interests, a closer look at Leonardo's cognitive patterns suggests a different conclusion: he was likely an INTJ.

Ni – dominant

Da Vinci’s cognition was fundamentally vision-driven, not idea-hopping for stimulation. His notebooks reveal long-term conceptual frameworks rather than spontaneous brainstorming. He wasn’t asking “what else could this be?” (Ne), but “what is the underlying principle that explains all of this?”

His work consistently sought unifying truths: how anatomy explains motion, how light explains beauty, how mechanics explain life. This is classic Ni — compressing reality into elegant internal models. Many of his projects spanned decades, evolving slowly as his internal vision sharpened. That level of singular, future-oriented synthesis is far more Ni than Ne.

Te – auxiliary

Despite the “artist” label, da Vinci was intensely pragmatic in execution. He documented experiments, measured proportions obsessively, tested hypotheses, and iterated designs with real-world constraints in mind. His engineering sketches weren’t abstract musings; they were actionable blueprints.

He worked multiple commissions simultaneously, optimized workflows, and applied his insights directly to warfare, architecture, and infrastructure. This wasn’t playful ideation — it was results-oriented system building, a strong Te pairing with Ni vision.

Fi – tertiary

Da Vinci was notoriously private, emotionally reserved, and resistant to external moral or social expectations. He didn’t marry, didn’t publicly justify himself, and showed little interest in conforming to societal roles. His values were internal, not performative.

His lifelong loyalty to a small inner circle (especially Salai) and his refusal to compromise artistic integrity — even when it cost him patrons — suggest a quiet but firm Fi core. He followed his sense of meaning, not public approval.

Se – inferior

While highly observant, da Vinci struggled with follow-through and present-moment closure. Many projects remained unfinished, not due to lack of ideas, but because execution in the physical world lagged behind his evolving inner vision.

His fascination with sensory detail (muscle fibers, water flow, facial expressions) reads less like Se dominance and more like inferior Se obsession — periods of intense immersion used to feed Ni insights, often at the expense of deadlines and practicality.

Why not ENTP?

ENTPs lead with Ne — rapid external idea generation, conversational exploration, social experimentation. Da Vinci, by contrast, was introspective, solitary, and internally driven. His creativity wasn’t sparked by external dialogue but by prolonged isolation, observation, and refinement.

Yes, he had many interests — but breadth alone does not equal Ne. INTJs often appear “scattered” when their Ni vision spans multiple domains that all serve the same internal model.

Context matters.

We should not forget that Leonardo da Vinci was an extreme outlier in intelligence, curiosity, and opportunity. Genius muddies type expression. A highly gifted INTJ — especially one operating in the Renaissance without modern specialization — can easily appear ENTP on the surface.

In reality, many high-Ni INTJs struggle with completion because their internal standard keeps evolving faster than the external world can keep up. This struggle with closure is not unique to Leonardo. His rival, Michelangelo, was so protective of his internal standards that he reportedly burned large quantities of his own drawings and sketches in bonfires toward the end of his life, determined that no one should see the "labors" he deemed inferior. For the high-Ni INTJ, the unfinished work isn't always a failure of effort; it's often a refusal to let the imperfect represent the vision.

Additionally, historical figures are frequently mistyped due to stereotype bias: polymath = Ne, artist = P, unfinished projects = perceiver.

Historical Figure MBTI

Historical Figure MBTI